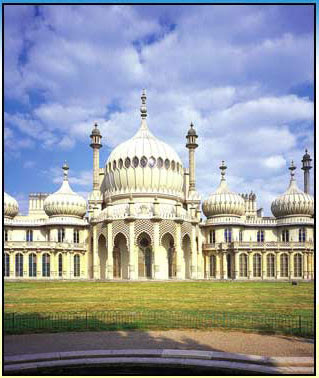

The Royal Pavilion, Brighton (1817–1822), “a grand oriental fantasy” with Indian domes and minarets and Chinese interiors, is a fascinating example of the diverse architectural styles allowed in the Regency period, which was otherwise dominated by refined neoclassical architecture. Two elements were necessary for its realization: an esthetically adaptable architect—in this case, John Nash (1752–1835)—and a client powerful enough to get what he wanted—the Prince Regent (later King George IV, 1762–1830), More importantly, it is probably the first attempt by any architect, freed from classical and Gothic precedents, to use cast iron to make legitimate architecture.

George, Prince of Wales, first visited the coastal resort of Brighton (then Brighthelmstone) in 1783. He was already deep in gambling debts, a heavy drinker, and a notorious womanizer. In 1784 he again visited Brighton and in the same year fell in love with the twice-widowed Maria Fitzherbert. When she refused to become his mistress he agreed to marry her, but secretly, because English law prohibited royalty from marrying Catholics. Two years later his comptroller, Louis Weltje, obtained from Thomas Kemp, Member of Parliament for Lewes, a three-year lease with an option to purchase on a timber house facing the sea at Brighton. He relet it to the prince, undertaking to rebuild it. Between May and July 1787 the architect Henry Holland enlarged and converted the modest but “respectable” farmhouse to the Marine Pavilion, a double-fronted Palladian affair with a domed Ionic rotunda. Maria was provided with a nearby villa.

In 1795, attempting to persuade Parliament to pay his accrued debts of £650,000, the prince entered a political marriage to his cousin, Caroline of Brunswick. After a daughter was born in January 1796 the royal couple lived apart. Caroline returned to Germany and George to the arms of Mrs. Fitzherbert. He moved his court to Brighton, where he planned the next stage of his evolving seaside house. Henry Holland was engaged on the other side of the country, so his assistant P. F. Robinson supervised the mutation of the Marine Pavilion’s interiors into a Chinese palace. The prince bought imported Chinese furniture and porcelain and even costumes, and from about 1802 chinoiserie interiors were executed by the firm of John Grace and Sons.

A year earlier George had directed Holland to design Chinese exteriors for the house, and in 1805 Holland’s successor William Porden made similar plans. The prince’s imagination was then seized by a new house, Sezincote in Gloucestershire (architect Samuel Cockerell), in the “Moghul” style. In 1807 Humphrey Repton, the landscape architect for Sezincote, was commissioned to design an Indian exterior for the Marine Pavilion. Although George liked the result, he could not afford to build it. But he had Porden construct a huge circular stables and riding house west of the house; crowned with a central cupola, it was in the Indian style.

In February 1811 King George III again retreated into madness, and the prince was appointed Regent. Breaking his promises to the Whigs, he supported the incumbent Tory government. He also disappointed Repton, who expected to complete the pavilion when his client had sufficient funds. Instead, in 1812 the commission was passed to James Wyatt. But he died in September 1813, and there was another hiatus until January 1815, when George capriciously engaged Repton’s sometime partner John Nash, who had designed London’s Regent Street and Carlton House Terrace (both 1813) for him.

The eclectic Nash swathed the exterior of Holland’s building in a mixture of pseudo-Moghul and neo-Gothic detail; internally, he changed it beyond recognition. The house is symmetrical about a long north-south axis. A central porte cochere on the west front enters through a vestibule, across a long gallery into a domed salon, flanked with drawing rooms at the “back” of the house. The prince’s apartments are in the northwestern wing of the first floor; visitors’ apartments occupy the southwestern wing. Above are “small but elegant” bedrooms. The banqueting hall, its opulent decor designed by Robert Jones and Frederick Grace, is in the southeastern corner. From a cluster of plantain leaves at the center of its 45-foot-high (14-meter) blue saucer dome hangs a gigantic gilded dragon gasolier. The walls are decorated with Chinese motifs in brilliant colors. The music room, also by Jones and Grace, is at the other end of the first floor. Its domed ceiling is formed by gilded scallop shells above an octagonal cornice, supported by dragon brackets; the walls and drapes are gold and crimson. It is possible to describe the disposition of spaces, but their scale and extravagant splendor must be experienced.

The roof is a fantastic agglomeration of domes, tentlike roofs (over the banqueting hall and music room), chimneys disguised as minarets, and “oriental” finials. Nash adventurously used cast iron in the structure and the interior and exterior details. The huge central ogee dome over the salon, and the other roofs, as well as the bases of the chimneys and pinnacles, are framed in the new material. The extremely ornate palm-tree columns supporting the roofs of the drawing rooms are also cast iron, as are the four simple, slender columns with copper palm-leaf capitals that carry the central roof lantern in the kitchen. The double staircases at either end of the long gallery are cast iron, too, but their balustrades and other details (like the wall mirrors throughout the house) are disguised with paint as bamboo, befitting the Chinese mood. Outside, iron was used for the elegant lattice tracery on the east front of the music room.

The diarist John Wilson Croker visited the Royal Pavilion before it was finished and declared it an “absurd waste of money,” accurately prophesying, “[it] will be a ruin in half a century or more.” The affairs of state limited George IV’s visits to his extravagant “pleasure dome.” His dissolute lifestyle eventually overtook him; addicted to alcohol and laudanum, he began showing signs of insanity, and shortly before his death he became increasingly reclusive. His successor, William IV (reigned 1830–1837), used the pavilion, but Queen Victoria acquired a summer home on the Isle of Wight. She sold the pavilion to the people of Brighton in 1850 after moving its furnishings to Buckingham Palace. It was put to various uses until, following World War II, interest in it was revived. Beginning in 1980 the storm-and fire-ravaged building was refurbished by the Brighton Borough Council, and Queen Elizabeth II returned most of the original furnishings. The Royal Pavilion, its splendor restored, was reopened to the public in 1990.

No comments:

Post a Comment